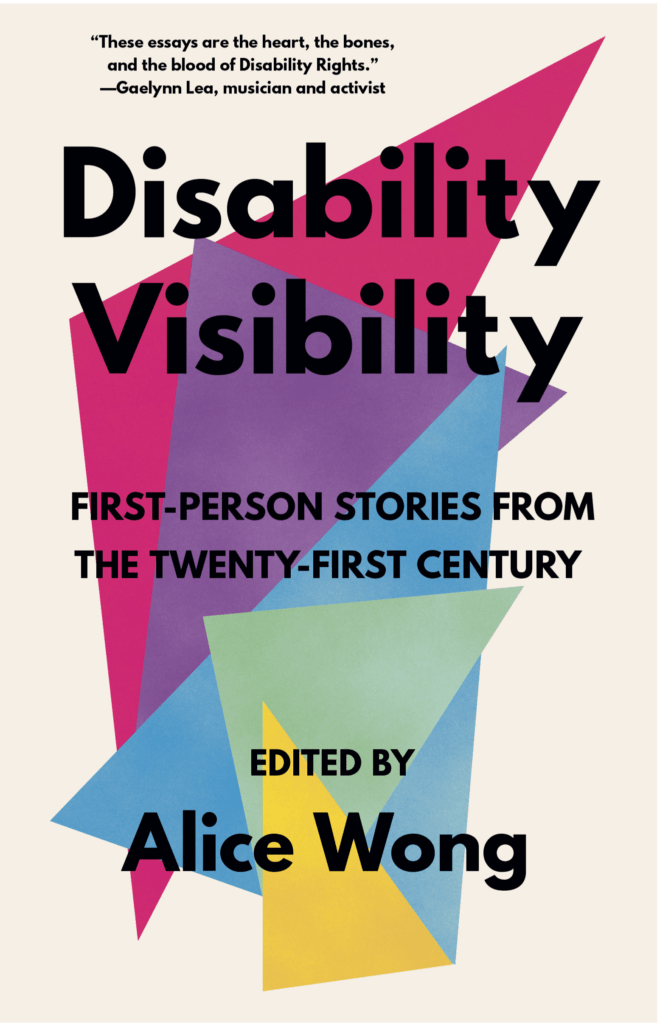

Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century (Vintage Books, 2020) is a collection of essays and other writings by disabled people. This is not a book of oral histories or a book that uses oral history as a method, but it’s nonetheless an important book for oral historians.

To clear up any confusion, there is an oral history project called the Disability Visibility Project Interviews, but the book Disability Visibility does not contain those oral histories. Both the oral histories and the book are projects by disability activist, writer, and MacArthur genius grant recipient Alice Wong.

Why should oral historians care about this book, which does not contain oral histories? The book’s subtitle, “first person stories from the twenty-first century,” suggests that Wong’s goals and the goals of oral historians are aligned. In the introduction to Disability Visibility, Wong describes her lifelong habit of collecting stories from and about disabled lives. She has found stories in newspapers, online, and, eventually, through her oral history project. “My collection led me to community,” she writes.

Indeed, Disability Visibility reflects the disabled community Wong has worked to build and maintain throughout her career. Reading Disability Visibility through an oral history lens led me to ask how our work as oral historians might change if we were to make community building a more foundational part of our practices. Perhaps our work would include more mediums, just as Wong’s includes both oral history recordings and written pieces. Perhaps we would be inspired to work more collaboratively across disciplines.

The first essay in the collection comes from the late attorney and disability rights activist Harriet McBryde Johnson, originally published in 2003. Johnson chronicles her encounters and public debates with influential philosopher and professor Peter Singer, who advocates for both infanticide of some disabled infants and assisted suicide for disabled adults. Johnson writes with humor and deep reflection about what it was like to debate her own right to exist and how her decisions about the situation were both informed by and affected her disabled community members. It’s a gripping essay, and it sets up the rest of the book by showing that disabled activism has been happening in community for decades.

From there, the book offers a range of stories from disabled thinkers with many different experiences of disability. The book centers perspectives from queer disabled people and disabled people of color. The pieces are arranged into four sections: Being, Becoming, Doing, and Connecting. Through these essays, we experience first-person perspectives on fasting for Ramadan and on cerebral palsy, disability and parenting, the frustratingly meandering and often unsafe New York City Access-a-Ride program, disability and climate catastrophe, and much more.

The pieces also take many forms. “For Ki’tay D. Davidson, Who Loves Us,” is the eulogy for Ki’tay D. Davidson, a Black disabled trans man, given by his partner. This piece demonstrates another strength of Disability Visibility: its dedication to preserving ephemeral pieces of disabled culture. Davidson’s eulogy, preserved and circulated in print, will be read and kept in living people’s memory. Posting a copy of the eulogy online or even adding it to a formal archive would probably not have the same combination of reach and longevity. Similarly, many of the essays in Disability Visibility are reprints, including many that are reprinted from online publications. Like oral history recordings, Wong’s book serves as a way to make ephemeral stories, at risk of disappearing as websites disappear, more durable.

The Disability Visibility Project and the Disability Visibility book offer models of collecting and disseminating disability-specific stories through more forms and genres: a queer crip clothing manifesto, an interview transcript that reflects the interviewee’s AAC (Augmented or Alternative Communication) use, a corrective addendum to the “Vision for Black Lives,” a formally experimental exploration of cyborg identity. All of these are complete pieces on their own, but they are made more powerful collected into a diverse chorus of disabled voices.

One of the last essays in the book, “On the Ancestral Plane: Crip Hand-Me-Downs and the Legacy of Our Movements” by Stacey Milbern, describes the author’s relationship to a pair of “crip socks” that were originally made for the aforementioned Harriet McBryde Johnson, passed on to Johnson’s friend, poet and disability activist Laura Hershey, and eventually inherited by Milbern. This essay brings the reader back to the beginning of the collection and reminds us that disabled lives and culture are continuous and interdependent. The focus on legacy insists that disabled stories are worth collecting, sharing, and retelling.

We oral historians can learn from Alice Wong’s expansive, collaborative approach to stewarding community and, through community, creating and curating culture. Wong isn’t an oral historian who set out to create an oral history project about disabled people. Rather, she is a highly networked disabled writer and activist whose goal is to promote disability culture. To me, it seems like the shape of her projects stem from her relationships and collaborations with other disabled people. If her community requires a book, she makes a book. If her community requires an oral history project, she makes an oral history project. And so on.

Disability Visibility feels like a lovingly assembled bibliography of contemporary disabled thinkers. Considered alongside the Disability Visibility Project oral histories, the book offers rich and multiple contexts through which listeners can understand the oral history recordings. I think of oral history at its best as a means of cultural creation that sits next to and converses with books, films, music, criticism, art, partying, theory, dance, and all other forms of cultural creation. Disability Visibility the book asks oral historians to consider the medium through which they create and curate. It pushes us to consider what cross-disciplinary collaborations might make our work more effective, more accessible, and more welcoming.

-Kae Bara Kratcha

Columbia University Libraries

Also read: Disability Intimacy: Essays on Love, Care and Desire, a second collection edited by Alice Wong that includes oral history interviews, and is reviewed in the latest issue of the Oral History Review.