Vanderbilt makes available the extraordinary Phil Schaap Jazz Collection

Because the development of jazz coincided with the inventions of recording and broadcasting, its story became an early oral history genre. Much of its history was told by the musicians who also played it, and many of their accounts were preserved on disc, tape and radio broadcasts, as well as in print.

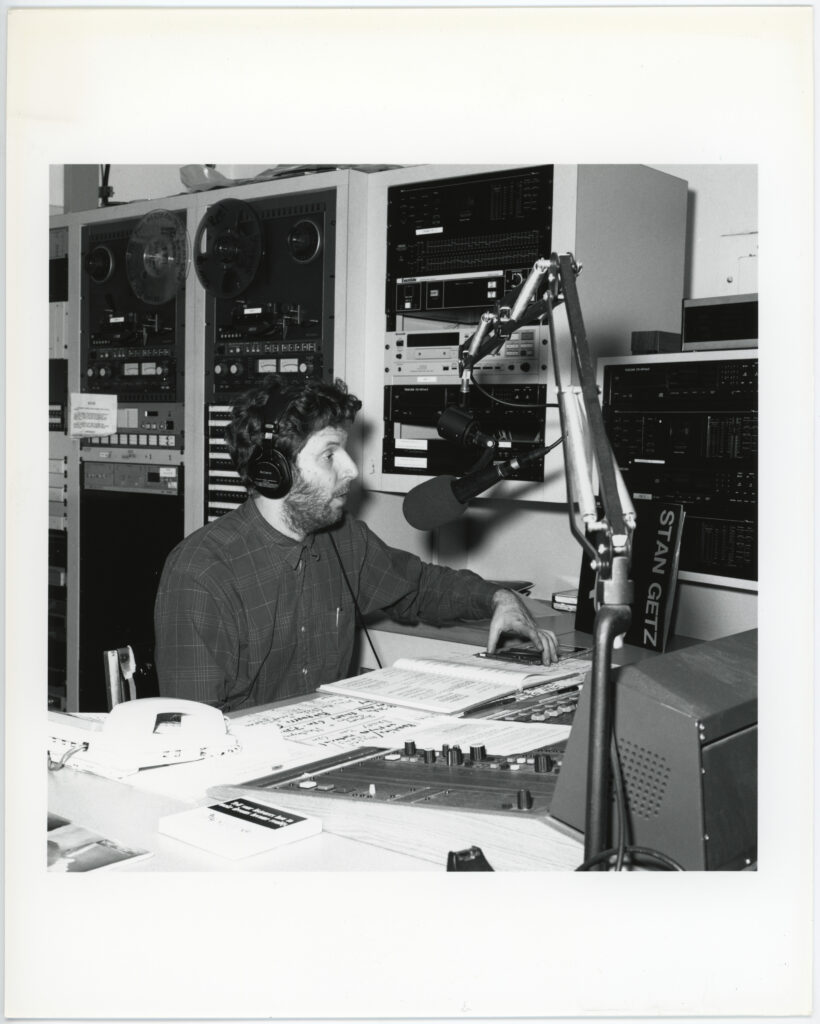

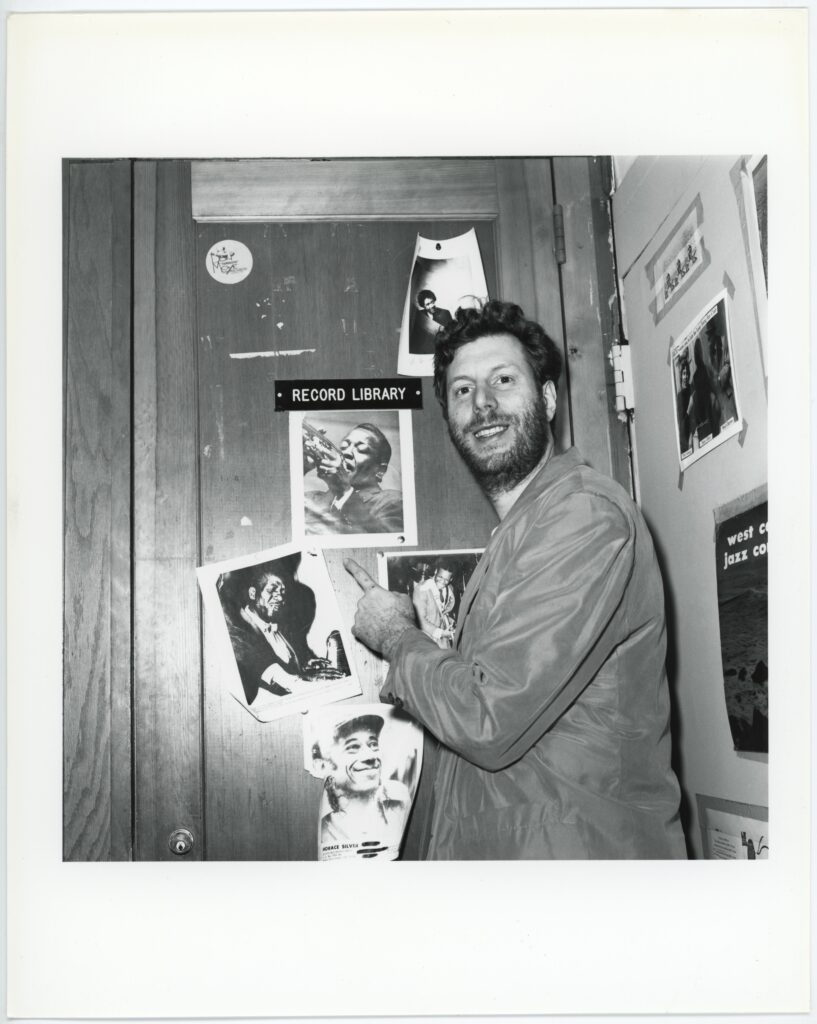

All of those media forms, along with many personal accounts of that history, are included in the Phil Schaap Jazz Collection, a monumental archive acquired last year by the Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries at Vanderbilt University in Nashville that is now becoming available to the public. Schaap, who worked for half a century as a disc jockey at WKCR-FM, Columbia University’s radio station, had a voice and an endlessly encyclopedic knowledge that were familiar to jazz-loving New Yorkers. His personal history was unique: even as a child he befriended musicians, including many who lived in Queens, borough where he grew up and lived until his death in 2021. His lifelong devotion to jazz and its players was complemented by his photographic memory, and over decades he enthusiastically shared his granular knowledge of recording dates and personnel on the radio and in interviews, in classrooms at Juilliard, Princeton, and Columbia, and in record albums, liner notes, and other publications.

Besides accumulating innumerable facts, Schaap also collected things, evidence of his musical passions. In its volume and scope his collection is as unique as he was. “We had about a thousand boxes of different sizes come in,” says Jake Schaub, Music Cataloging Librarian at Vanderbilt’s Anne Potter Wilson Music Library, where the Schaap collection will be based. The boxes contained “between three and four thousand tape reels,” Schaub estimates, “about a hundred boxes of papers and other things,” and about “26,000 published recordings” on LPs, 78s, CDs and cassettes. Says Schaub, “It’s a matter of debate at the university whether any of us have dealt with anything of this size before.”

Oral historians will be particularly interested in the interviews in the collection. “We have about 1,600 unique interviews that we’ve tracked down so far,” says Schaub, with or about musicians from every era of jazz, including Max Roach, Benny Carter, Gerald Wilson, Charles Lloyd, Lee Young, John Lewis, Joe Bushkin, Yusef Lateef (whose archive is also housed at Vanderbilt), and many others. On some of the recordings, words and music meet. Schaap often recorded off-the-cuff conversations with veteran musicians during set breaks at the West End bar in Morningside Heights and other New York City venues, gigs that he organized and broadcast beginning in the 1970s.

Since acquiring the collection last year, Vanderbilt’s library has already made close to 1,900 items available to the public, many of them via the Aviary platform, with new things added every week. “We’re digitizing like crazy,” Schaub says. In addition, interviews and other audio material that previously had been posted on Schaap’s personal website will appear on the Vanderbilt site. As the materials are made available, the library is honoring Schaap’s pursuit of every musical format. “We’re putting the published sound recordings in our library catalog” says Holling Smith-Borne, Director of the Wilson Music Library. “There’s a process to request them to be digitized, which I think most of our students prefer. But we have playback equipment in the music library, so if they wanted an authentic experience to play an LP or 78, we could do that.”

There are further plans to develop the Schaap archive, which was obtained via a Vanderbilt initiative called the Academic Archives Purchasing Fund, which allows the university to acquire collections for research and exhibit in conjunction with the National Museum of African American Music, also in Nashville, with the goal of supporting “ongoing and potential scholarship on African American music.” The library is seeking additional funds to create a listening room, where visitors could further engage with Schaap’s materials. “I foresee a lot of community programming,” says Smith-Borne, “maybe some jazz sessions there.”

Because so many of the materials includes Schaap’s voice, the collection in some ways comprises his oral history. “You can tell from his interviews he was really energetic,” says Smith-Borne. Schaub concurs: “I listened to some of those West End recordings, and at the beginning he introduces everyone, and somehow he knows everyone’s birthday on the bandstand.” Schaap’s boundless devotion to bebop saxophonist Charlie Parker is also well represented by “at least 2,000” entries of “Bird Flight,” his weekday radio show in which he meticulously scrutinized the life and music of Charlie Parker. There is hard evidence of his fascination with the musician. “We have a rock that he dug up from the house where Parker grew up,” says Schaub. “It sheds quite a light on the personality and the dedication and determination of Phil Schaap that he would go to the lengths of getting a shovel and digging up a rock at Charlie Parker’s childhood home.”

The spirit of Schaap’s archive reflects goals common to all oral historians–how to adequately gather, preserve, and share knowledge and memories. But if recording and collecting were his private passions, he also worked publicly, using the broadcast medium, always with posterity in mind. (WKCR continues to re-broadcast his past shows.) In a memorable 2008 profile that appeared in The New Yorker, writer and editor David Remnick observed that Schaap put “his frenzied memory and his obsessive attention to the arcane in the service of something important: the struggle of memory against forgetting—not just the forgetting of a sublime music but forgetting in general.” Now available to new generations of listeners, Schaap’s archive ensures that his unique love for jazz facts and figures–his legacy–won’t be forgotten. He was “very intentional” says Smith-Borne about the collection. “He wanted it to have a good home.”

~Bud Kliment, Media Review Editor