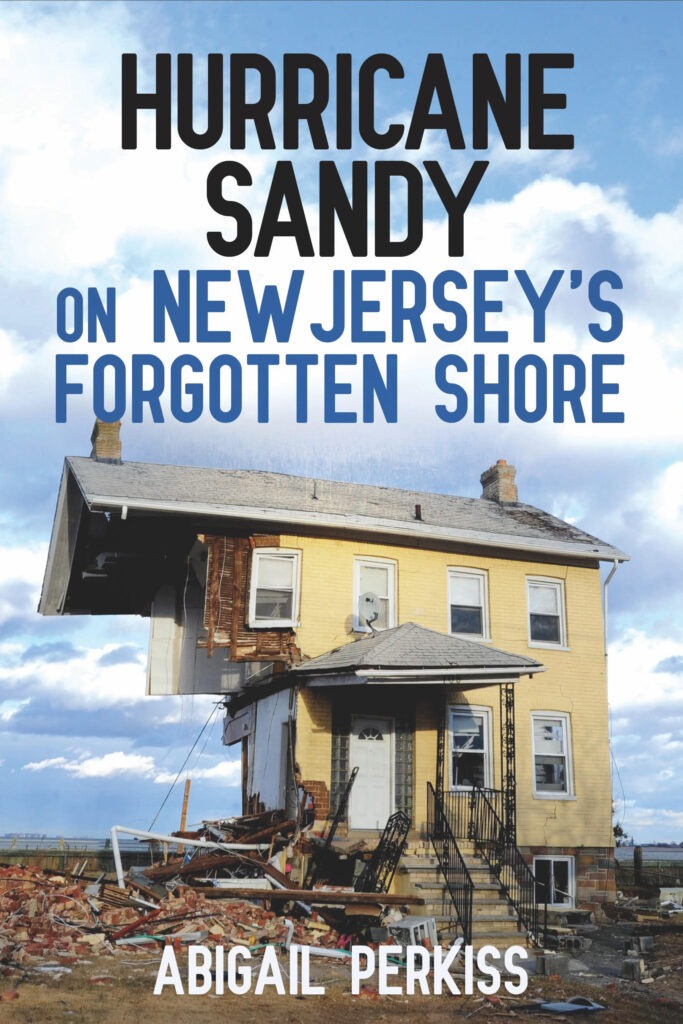

We ask authors of books reviewed in Oral History Review to answer 5 questions about why we should read their books. In our latest installment of the series, former co-editor, Abigail Perkiss, discusses her book, Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore, which is reviewed in the latest issue of OHR.

Give us the elevator pitch for your book. What’s it about and why does it matter?

The relationship between human action and natural hazards has become one of the most pressing issues of our time, with weather’s increasing ferocity across the globe, political debates over the nature of climate change, and the ongoing need to manage the impact of environmental conditions on the built environment.

While debates and policy decisions capture headlines, individual voices often get lost. Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore recovers those voices. Drawing on nearly seventy oral history interviews that my students and I conducted in the three years following Hurricane Sandy, it documents the uneven recovery from the storm along the Raritan and Sandy Hook Bays, neglected areas of New Jersey’s shoreline.

How does oral history contribute to your book?

In January 2013, just three months after Sandy made landfall, I met with a group of six undergraduate students at my university in an advanced public history seminar. My plan was to work with these students to develop an oral history project to document the storm and its aftermath – even as my students had no experience in oral history and I had little in the way of directing a large-scale project. While we were all inexperienced, we learned together, and over the months – then years – that followed, we collected more than seventy interviews with residents and business owners from New Jersey’s Bayshore region, 115 miles of coastline running from Sandy Hook at the lip of the Atlantic Ocean to South Amboy at the mouth of the Raritan River. These interviews form the narrative backbone of this book: the experiences and perspectives that our narrators offered drive forward the story of the storm and the recovery.

The shared stories shed light on the short-term preparedness initiatives that municipal and state governments undertook, which successfully mitigated the risk to human life, but also the long-term planning decisions that created the conditions for catastrophic property damage. They honor the role of local and national media outlets in galvanizing recovery efforts, but they also call out the feelings of marginalization for those residents whose communities the television cameras ignored. They illuminate the ways in which Hurricane Sandy remade the role of social media in disaster preparedness and recovery. Finally, their voices ask the hardest questions about the equity of the rebuilding, and they lay bare the ways that climate change and sea-level rise are creating critical vulnerabilities in the most densely populated areas in the nation

What do you like about using oral history as a methodology?

I became a historian because I was drawn the intersection of history and memory: how our understanding of the past shapes our contemporary predicament, and how our contemporary context informs how we understand and interpret the past. And I have found oral history to be one of the most powerful vehicles through which to understand that relationship.

Practicing oral history as a student, teacher, scholar, and editor – I’ve discovered that I also love that the field is still emerging and evolving, that our methodologies change with new technologies and new intersections with other fields. In the years since these interviews were conducted, I have spent much time reflecting on the connections between oral history and trauma, particularly as it impacts the oral historian interviewer. This work has taken me in new directions – collaborating with scholars across disciplines to develop resources for oral historians working in crisis situations, and putting me in conversation with others who are doing important work on trauma-informed oral history. I love the nimbleness and responsiveness of our field and the collective will to do better.

As a result, the Oral History Association has become my professional home, and many of its members are now my good friends. Doing this work means I get to keep coming back!

Why will fellow oral historians be interested in your book?

Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore is steeped in oral history, both substantively and methodologically. Beyond the story of the storm itself, the final section of the manuscript is an essay detailing the origins story of the oral history project that I undertook with my students – what we called Staring out to Sea – and aims to provide a roadmap for other practitioners and teachers interested in doing this work.

What is the one thing that you most want readers to remember about the book?

This is such an interesting question. On one level, I want readers to remember the individual characters – the individual people who shared their stories with us. They include: Linda Gonzalez, who penned poems by candlelight as rain and wind beat down on her beloved Union Beach, knowing that those might be the last moments of relative calm that she would experience for months; James Butler, who erected a washed-up plastic Christmas tree at the corner of Jersey Avenue and Shore Road and became a national icon representing “Jersey Strong”; Mary Jane and Roger Michalak, married forty-seven years, who realized that they wouldn’t be able to raise themselves through a hole in their attic and instead sat down on their bed together, waiting for the water to wash over them; and so many others. Such voices, individually and collectively, offer a portrait of a devastating storm and of the network of relationships as victims, volunteers, and state and federal agencies came together afterward to rebuild.

But I think the biggest takeaways come when we step back and look the story more broadly. Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore isn’t a comprehensive evaluation of the storm. It’s not a blueprint of post-disaster response, nor a polemical treatise on what went wrong. Instead, the book offers an intimate window into the human impact of a devastating hurricane, and the intended and unintended consequences of long-term policy decisions that created the conditions for such destruction. It sheds light on the individual choices that residents made in the days preceding landfall, and the personal dilemmas they faced as they struggled to rebuild their lives. Out of these individual stories emerges the larger story of the Bayshore itself – the land, the waterways, the homes and businesses and community spaces, told by the people that inhabit them.