The Sioux Indian nation, Southern black gay men and San Francisco’s queer community in the 1940s might appear to have little in common.

But three scholars featured in an OHA conference plenary session illustrated how oral history can cross a multitude of disciplinary boundaries.

Over the years, said moderator Donald A. Ritchie, a past OHA president, “We’ve had just about every possible use of oral history.”

Nan Alamilla Boyd, professor of women and gender studies at San Francisco State University, said she was warned against trying to write her dissertation in the 1980s about the history of San Francisco’s queer community. For her, oral history was not merely a methodology; it was essential because so few print sources documented information about the 1940s sex workers and cross-dressers in San Francisco that were among the sources for her historical research.

She attempted to establish historical credibility for the interviews with such sources by cross-referencing them against each other.

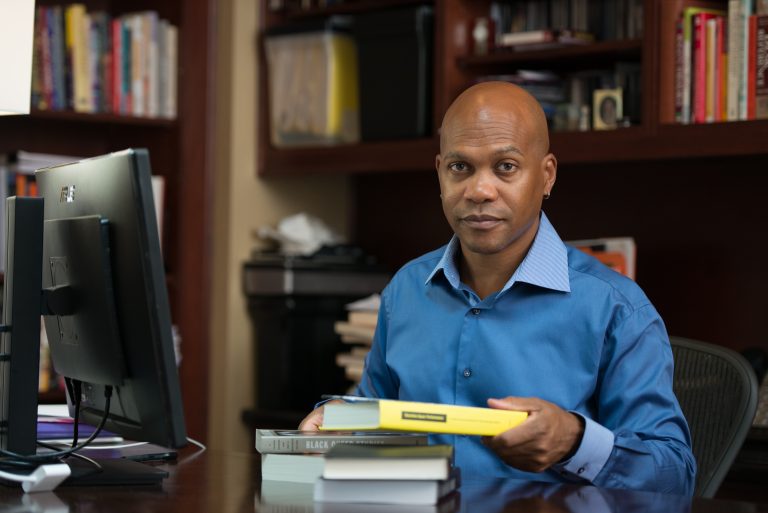

With a somewhat similar focus on race, gender and sexuality, performance artist E. Patrick Johnson used oral history in his doctoral dissertation—the story of his grandmother’s life as a live-in domestic for a Southern white family.

Johnson created a one-man show based on stories of black gay men in the South and is working on a companion project based on oral history interviews with Southern black women. Most of the women who have been interviewed report having experienced sexual trauma at the hands of a male family member, Johnson said, noting that telling one’s story in an oral history interview is a way of validating that story.

Moreover, he added, using those stories in an oral history performance has “healing potential.”

For historian and human rights activist Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, oral history also emerged in a federal courtroom.

Dunbar-Ortiz was recruited by American Indian lawyer, author and activist Vine Deloria Jr. to be an expert witness on a motion to dismiss charges against nearly 300 defendants, mostly members of the Sioux nation from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, in the aftermath of the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

Dunbar-Ortiz, serving on the legal team as well as in her role as an expert witness, recalled how the testimony by tribal elders evolved into “an extraordinary oral history” of the Lakota people. “There is a lot of rich oral history in court testimony,” she said.